Historic Figures

WITH THE NAME HENRY

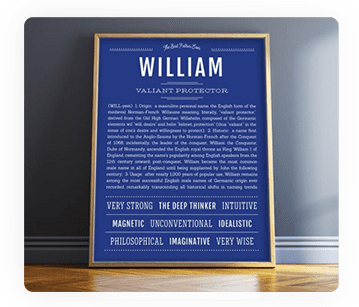

William Henry Harrison was America’s ninth president, serving for only one month from March 4 to his death on April 4, 1841. Harrison made a name for himself as the hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe against Native American Indians who fought against American expansion within the Indiana Territory (um, can you blame them?). Well, back then Harrison was highly regarded for his actions and ran his campaign on the famous "Tippecanoe and Tyler, too" slogan. Harrison also has two other distinctions: he was the last President born a British subject and he was the first President to die in office. Ironically, Harrison contracted pneumonia during his two hour long inaugural address on a cold January winter's day (his First Lady Anna was not in attendance). William is a name of Germanic origins and means "valiant protector" (he should have protected himself from that cold!) Harrison is also a fairly commonly used male given name in America.

Known also as Henry of Bolingbroke, Henry IV ascended to the throne after his cousin Richard II was deposed (this Henry was the grandson of Edward III). He immediately had to deal with rebellions by both the Welsh and those closer to home and his reign was riddled with plots against him. There’s nothing too notable about Henry IV other than his participations in the on-going Crusades and the War of the Roses, but really didn’t accomplish much. He was also the first native English-speaking king (his predecessors had spoken French).

King Henry V was the son of Henry IV and ascended the throne upon his father’s death. He is known as one of the greatest of all English monarchs and a bane to the French existence. First, Henry V successfully seized the northwest French post, Harfluer. It was an uneven battle and so a massive victory, as the French outnumbered the English by thousands. It was a heady victory for the young king who was met with much fanfare after returning to London. He wasn’t done yet, though. In 1420, he returned to capture Normandy which resulted in the signing of the Treaty of Troyes, naming Henry the heir to the French throne. He celebrated by marrying the daughter of the then-King of France, Charles VI. Her name was Catherine, and she would bear Henry, a son soon to become King Henry VI (and soon to undo his father’s fine work). Henry V’s life was cut short in his mid-30s (struck down by dysentery).

Henry VI not only ascended to the English throne at the age of nine-months, but at the ripe old age of one, he also was king of France. Too young, his uncles would serve as regents and more royal family members would crawl out from the woodwork with their greed for power. About the only good that came out of this naive king’s reign was a passion for education and building (Eton College and King’s College were erected during his time). Turns out, Henry VI’s biggest problem would be a French peasant girl by the name of Joan of Arc. According to her story, which she shared with the Dauphin of France, the voices of the Saints Michael, Catherine and Margaret told her that she alone could drive the English out of France. We can just imagine that the poor, hapless Dauphin unable to motivate the French people himself, responded with a resounding “Sweet, dude. Go for it!†So little Joanie throws on her amour, jumps on her white horse, and heads for Orleans. Her zealous faith in the “Lord’s wishes†and her firm belief in her own purpose must have rubbed off on the people who joined her one-person uprising, because the English would eventually exit stage left. (For more on Joan, see the name Joan). The English and the French are still amidst the 100 Years’ War, but we are nearing the end now. Henry VI mad a terrible mistake by not taking France’s offer of Normandy and Aquitaine if they would just get the hell out, because the French would eventually recapture all of their land back. Of course, this was not Henry’s only problem. Back at home, he wasn’t so popular, particularly given the miserable losses to the French. Enter Richard of York (Henry’s cousin) who was seen as an arguably more legitimate heir to the throne than the current king, fast-forward to The War of Roses, in which two distinct lineages fight over the monarchy for the next 30 years. They brought new meaning to the term dysfunction families. And their battles with one another were seriously violent. Henry VI would ultimately be captured and killed, and the Duke of York’s son would become King Edward IV of England, thus transferring the monarchy to a new House (Lancastrians to the Yorks).

The War of the Roses came in with a Henry, and it went out with a Henry. Henry VII waged the last and final battle of this war when he overthrew King Richard III in 1485 and became the first monarch from the House of Tudor (which turned out to be a long-lasting dynasty). Henry VII was the cool-headed, able king who ushered England into the modern era. Although he was a Lancastrian, he was so by illegitimate descent through King John. He united the Yorks with the Lancasters by marrying Edward IV’s daughter, Elizabeth – so now everyone is neatly together under the new House of Tudor, by a little stretch of the imagination. Still, Henry VII was a fine ruler, although not beloved by the people (he kept his distance from the common man). Under Henry VII, the English government came to be more stabilized and centralized and he died leaving a peaceful and prosperous England to his incurable pleasure-seeking, tyrannically arrogant, hot-headed son, none other than the legendary King Henry VIII.

It will be difficult to summarize this one, so we’ll try and stick to the key facts, and the interesting parts. He became king at the age of 17 after his father died. He loved all forms of leisure and pleasure (hunting, food, wine, music, poetry), but most of all, he liked the ladies (he holds the record for royal marriages). His first wife, Catherine of Aragon, gave birth eight times but produced only one surviving daughter (Mary). Intent on a male heir, Henry VIII decided he needed a new wife. All he needed was the pope to grant him an annulment; only problem was that the Holy Roman Emperor was Catherine’s nephew and she had no intentions of letting this happen. The pope, in turn, could not risk upsetting Rome’s ruler, so the pope did nothing. Furious, Henry VIII severed all connections with the Catholic Church of Rome, had an English Archbishop grant his annulment, and married Anne Boleyn (mother to the future Queen Elizabeth I of England). Well, the pope was having none of that and turned right around and excommunicated the king. What did Henry get for all of his troubles? Another daughter [it’s hard not to laugh at this point]. Stubborn Henry then makes himself “Supreme Head†of the Church of England and goes around beheading any dissenters (you’ll notice his penchant for beheading people a little later). “My way or the highway†best sums up this man’s reign. Back to Anne who wasn’t able to produce a son. Henry, frustrated and tired with poor Anne, moves onto her lady-in-waiting, Jane Seymour (he has Anne beheaded on trumped up charges of treason for…get this…unfaithfulness). Now that’s the pot calling the kettle black! Good ole Jane manages to capture one of those Y chromosomes and gives birth to a son, much to Henry’s delight (but she dies 12 days later from complications). Next, enter: Anne of Cleves, a marriage that was prearranged. When they finally meet for the first time in person, the disappointment is mutual. Anne was reportedly plain, boring and acne-scarred. Henry was no Don Juan himself at this point in his life, grossly overweight and generally nasty. He had that one annulled seven months later, and those he could find to blame for the disastrous pairing were promptly beheaded. Anne of Cleves got to keep her head, and Henry did pay spousal support. After Anne of Cleves came Catherine Howard, a beautiful 18 year old (to Henry’s 49). Enamored with the young sprite at first, Henry wasted no time demanding “Off with her head!†when he learned of her extramarital affairs. Last but not least, we have Catherine Parr (the man liked the name Catherine, apparently). She, too, was young (31), but married the fat old king more from a sense of duty than an aspiring interest in social status and wealth, and she was good to him. She was the one that was there to the end, and he named her Regent before dying at the age of 55. Detestable in so many ways, you have to admit, Henry VIII was one colorful character.

King Henry I was the fourth son of William the Conqueror and the only one to be born in England. Henry succeeded his brother William II as King of England after William’s suspicious death during a hunting trip with his brother, um, Henry (convenient is a word that comes to mind). Henry had to then fight another older brother, Robert, for the throne which ultimately leads to Robert’s imprisonment. After securing his place on the throne, Henry went onto marry a Scot (Edith who would later be renamed Matilda), who was the great-granddaughter of Edward the Confessor, thus placating both the Scots and the Saxons. Henry received two nicknames during his reign “Beauclerc†(which is French for ‘fine scholar’) given his studious nature, and “The Lion of Justice†given his judicial reforms which established a balance for the Anglo-Norman traditions of his kingdom. For the most part, Henry reined during a period of peace and prosperity. He did leave one problem, though: Matilda only gave him two children: William and Matilda, Jr. The heir-apparent, William, died at the age of 17 in an unfortunate drowning accident, and Papa Henry was not too keen on his daughter ascending the throne. He married again (Matilda, Sr. had since died) in an effort to produce another male heir, but was unsuccessful. The throne eventually went to his nephew, Stephen. That would turn out to be a mistake because Matilda Jr. was one fiery bitch.

Henry II was Matilda, Jr.’s son and raised in France until the age of nine, returning with his mother to England in her effort to reclaim the throne. She never quite managed the coup for herself, but Henry II would ascend through her lineage upon Stephen’s death. Henry II had a few things going for him from the English perspective. He was the grandson of Henry I who had done a lot to integrate the Norman-Anglo ways into a fairly stable atmosphere, he was Scottish by way of his maternal lines, and he truly was the rightful heir to the throne. But he also had one glaring problem: his wife Eleanor. She was one tempestuous shrew. Eleanor actively plotted with their sons (Henry, Richard and Geoffrey) to rebel against their father, and she encouraged invasions by the kings of Scotland and France. Such a nuisance was she that Henry II would eventually place her under house-arrest for 15 years. Henry II was a man of reason and intellect like his grandfather and is notable for creating Common Law in England. Only problem was that Henry expected to extend these royal judicial oversights onto the Church. Big mistake. Big, big mistake. Henry appointed Thomas Becket as Archbishop of Canterbury, believing him to have like-minded ideals of exposing the judicial abuses rampant in the Church. What he didn’t expect is that Becket would about-face and side with the Church. Becket went into exile upon hearing the king’s intention to try him for contempt. When Becket returned to England six years later, Henry II screamed (probably rhetorically), “Will someone rid me of this turbulent priest?†Someone took him seriously, because a couple of his knights would go and kill Becket on (gasp) the alter during Church service (thereby martyring him). Needless to say, this event didn’t exactly serve to popularize the King among his people, and he was henceforth publically shamed (forced to walk barefoot through Canterbury, arrive at Becket’s tomb, beg for pardon, and receive a lashing). Not too dignified for a King, huh? His sons Richard I and then John I would succeed him in that order.

King Henry III was John I’s son and Henry II’s grandson. He inherited the throne from his father at the age of nine during another one of those pesky Civil Wars the English like so much (thanks, Dad). Not only was he an ineffective ruler, but he went through money like water after several unsuccessful invasions into Wales and France, and prompted rebellions among the barons (who forced him to limit his powers by signing the “Provisions of Oxfordâ€). The first Parliament (or so considered) convened during his reign, in reaction to this repudiating king. The Baron’s War would ensue leading to the king’s capture and his ultimate escape from captivity orchestrated by his son, Edward, who would eventually succeed his hapless father.

Known also as Henry of Bolingbroke, Henry IV ascended to the throne after his cousin Richard II was deposed (this Henry was the grandson of Edward III). He immediately had to deal with rebellions by both the Welsh and those closer to home and his reign was riddled with plots against him. There’s nothing too notable about Henry IV other than his participations in the on-going Crusades and the War of the Roses, but really didn’t accomplish much. He was also the first native English-speaking king (his predecessors had spoken French).

King Henry V was the son of Henry IV and ascended the throne upon his father’s death. He is known as one of the greatest of all English monarchs and a bane to the French existence. First, Henry V successfully seized the northwest French post, Harfluer. It was an uneven battle and so a massive victory, as the French outnumbered the English by thousands. It was a heady victory for the young king who was met with much fanfare after returning to London. He wasn’t done yet, though. In 1420, he returned to capture Normandy which resulted in the signing of the Treaty of Troyes, naming Henry the heir to the French throne. He celebrated by marrying the daughter of the then-King of France, Charles VI. Her name was Catherine, and she would bear Henry, a son soon to become King Henry VI (and soon to undo his father’s fine work). Henry V’s life was cut short in his mid-30s (struck down by dysentery).

Henry VI not only ascended to the English throne at the age of nine-months, but at the ripe old age of one, he also was king of France. Too young, his uncles would serve as regents and more royal family members would crawl out from the woodwork with their greed for power. About the only good that came out of this naive king’s reign was a passion for education and building (Eton College and King’s College were erected during his time). Turns out, Henry VI’s biggest problem would be a French peasant girl by the name of Joan of Arc. According to her story, which she shared with the Dauphin of France, the voices of the Saints Michael, Catherine and Margaret told her that she alone could drive the English out of France. We can just imagine that the poor, hapless Dauphin unable to motivate the French people himself, responded with a resounding “Sweet, dude. Go for it!†So little Joanie throws on her amour, jumps on her white horse, and heads for Orleans. Her zealous faith in the “Lord’s wishes†and her firm belief in her own purpose must have rubbed off on the people who joined her one-person uprising, because the English would eventually exit stage left. (For more on Joan, see the name Joan). The English and the French are still amidst the 100 Years’ War, but we are nearing the end now. Henry VI mad a terrible mistake by not taking France’s offer of Normandy and Aquitaine if they would just get the hell out, because the French would eventually recapture all of their land back. Of course, this was not Henry’s only problem. Back at home, he wasn’t so popular, particularly given the miserable losses to the French. Enter Richard of York (Henry’s cousin) who was seen as an arguably more legitimate heir to the throne than the current king, fast-forward to The War of Roses, in which two distinct lineages fight over the monarchy for the next 30 years. They brought new meaning to the term dysfunction families. And their battles with one another were seriously violent. Henry VI would ultimately be captured and killed, and the Duke of York’s son would become King Edward IV of England, thus transferring the monarchy to a new House (Lancastrians to the Yorks).

The War of the Roses came in with a Henry, and it went out with a Henry. Henry VII waged the last and final battle of this war when he overthrew King Richard III in 1485 and became the first monarch from the House of Tudor (which turned out to be a long-lasting dynasty). Henry VII was the cool-headed, able king who ushered England into the modern era. Although he was a Lancastrian, he was so by illegitimate descent through King John. He united the Yorks with the Lancasters by marrying Edward IV’s daughter, Elizabeth – so now everyone is neatly together under the new House of Tudor, by a little stretch of the imagination. Still, Henry VII was a fine ruler, although not beloved by the people (he kept his distance from the common man). Under Henry VII, the English government came to be more stabilized and centralized and he died leaving a peaceful and prosperous England to his incurable pleasure-seeking, tyrannically arrogant, hot-headed son, none other than the legendary King Henry VIII.

It will be difficult to summarize this one, so we’ll try and stick to the key facts, and the interesting parts. He became king at the age of 17 after his father died. He loved all forms of leisure and pleasure (hunting, food, wine, music, poetry), but most of all, he liked the ladies (he holds the record for royal marriages). His first wife, Catherine of Aragon, gave birth eight times but produced only one surviving daughter (Mary). Intent on a male heir, Henry VIII decided he needed a new wife. All he needed was the pope to grant him an annulment; only problem was that the Holy Roman Emperor was Catherine’s nephew and she had no intentions of letting this happen. The pope, in turn, could not risk upsetting Rome’s ruler, so the pope did nothing. Furious, Henry VIII severed all connections with the Catholic Church of Rome, had an English Archbishop grant his annulment, and married Anne Boleyn (mother to the future Queen Elizabeth I of England). Well, the pope was having none of that and turned right around and excommunicated the king. What did Henry get for all of his troubles? Another daughter [it’s hard not to laugh at this point]. Stubborn Henry then makes himself “Supreme Head†of the Church of England and goes around beheading any dissenters (you’ll notice his penchant for beheading people a little later). “My way or the highway†best sums up this man’s reign. Back to Anne who wasn’t able to produce a son. Henry, frustrated and tired with poor Anne, moves onto her lady-in-waiting, Jane Seymour (he has Anne beheaded on trumped up charges of treason for…get this…unfaithfulness). Now that’s the pot calling the kettle black! Good ole Jane manages to capture one of those Y chromosomes and gives birth to a son, much to Henry’s delight (but she dies 12 days later from complications). Next, enter: Anne of Cleves, a marriage that was prearranged. When they finally meet for the first time in person, the disappointment is mutual. Anne was reportedly plain, boring and acne-scarred. Henry was no Don Juan himself at this point in his life, grossly overweight and generally nasty. He had that one annulled seven months later, and those he could find to blame for the disastrous pairing were promptly beheaded. Anne of Cleves got to keep her head, and Henry did pay spousal support. After Anne of Cleves came Catherine Howard, a beautiful 18 year old (to Henry’s 49). Enamored with the young sprite at first, Henry wasted no time demanding “Off with her head!†when he learned of her extramarital affairs. Last but not least, we have Catherine Parr (the man liked the name Catherine, apparently). She, too, was young (31), but married the fat old king more from a sense of duty than an aspiring interest in social status and wealth, and she was good to him. She was the one that was there to the end, and he named her Regent before dying at the age of 55. Detestable in so many ways, you have to admit, Henry VIII was one colorful character.

King Henry I was the fourth son of William the Conqueror and the only one to be born in England. Henry succeeded his brother William II as King of England after William’s suspicious death during a hunting trip with his brother, um, Henry (convenient is a word that comes to mind). Henry had to then fight another older brother, Robert, for the throne which ultimately leads to Robert’s imprisonment. After securing his place on the throne, Henry went onto marry a Scot (Edith who would later be renamed Matilda), who was the great-granddaughter of Edward the Confessor, thus placating both the Scots and the Saxons. Henry received two nicknames during his reign “Beauclerc†(which is French for ‘fine scholar’) given his studious nature, and “The Lion of Justice†given his judicial reforms which established a balance for the Anglo-Norman traditions of his kingdom. For the most part, Henry reined during a period of peace and prosperity. He did leave one problem, though: Matilda only gave him two children: William and Matilda, Jr. The heir-apparent, William, died at the age of 17 in an unfortunate drowning accident, and Papa Henry was not too keen on his daughter ascending the throne. He married again (Matilda, Sr. had since died) in an effort to produce another male heir, but was unsuccessful. The throne eventually went to his nephew, Stephen. That would turn out to be a mistake because Matilda Jr. was one fiery bitch.

Henry II was Matilda, Jr.’s son and raised in France until the age of nine, returning with his mother to England in her effort to reclaim the throne. She never quite managed the coup for herself, but Henry II would ascend through her lineage upon Stephen’s death. Henry II had a few things going for him from the English perspective. He was the grandson of Henry I who had done a lot to integrate the Norman-Anglo ways into a fairly stable atmosphere, he was Scottish by way of his maternal lines, and he truly was the rightful heir to the throne. But he also had one glaring problem: his wife Eleanor. She was one tempestuous shrew. Eleanor actively plotted with their sons (Henry, Richard and Geoffrey) to rebel against their father, and she encouraged invasions by the kings of Scotland and France. Such a nuisance was she that Henry II would eventually place her under house-arrest for 15 years. Henry II was a man of reason and intellect like his grandfather and is notable for creating Common Law in England. Only problem was that Henry expected to extend these royal judicial oversights onto the Church. Big mistake. Big, big mistake. Henry appointed Thomas Becket as Archbishop of Canterbury, believing him to have like-minded ideals of exposing the judicial abuses rampant in the Church. What he didn’t expect is that Becket would about-face and side with the Church. Becket went into exile upon hearing the king’s intention to try him for contempt. When Becket returned to England six years later, Henry II screamed (probably rhetorically), “Will someone rid me of this turbulent priest?†Someone took him seriously, because a couple of his knights would go and kill Becket on (gasp) the alter during Church service (thereby martyring him). Needless to say, this event didn’t exactly serve to popularize the King among his people, and he was henceforth publically shamed (forced to walk barefoot through Canterbury, arrive at Becket’s tomb, beg for pardon, and receive a lashing). Not too dignified for a King, huh? His sons Richard I and then John I would succeed him in that order.

King Henry III was John I’s son and Henry II’s grandson. He inherited the throne from his father at the age of nine during another one of those pesky Civil Wars the English like so much (thanks, Dad). Not only was he an ineffective ruler, but he went through money like water after several unsuccessful invasions into Wales and France, and prompted rebellions among the barons (who forced him to limit his powers by signing the “Provisions of Oxfordâ€). The first Parliament (or so considered) convened during his reign, in reaction to this repudiating king. The Baron’s War would ensue leading to the king’s capture and his ultimate escape from captivity orchestrated by his son, Edward, who would eventually succeed his hapless father.

William Harrison was the 9th President of the United States, the last President to be born a British subject, the oldest President to be elected at age 68 (until Ronald Reagan), the President with the shortest term (one month) and the first to die in office. Elected in 1840, Harrison’s campaigned under the slogan “Tippecanoe & Tyler, too!†to remind Americans of his military prowess against American Indians in the Battle of Tippecanoe (1811). He is also noted for having the longest inaugural speech in history (over two hours!). Standing out in that east-coast cold January weather for so long at his inauguration ironically led to Harrison contracting pneumonia - he would die 32 days later. It was the first time in American history that Presidential Succession was put into force, and Vice President John Tyler would assume the office.

Patrick Henry was an American orator, politician and Founding Father who led the movement for independence in Virginia in the 1770s. He is most known for his "Give me Liberty, or give me Death!" speech. An impassioned promoter of the American Revolution and Independence, Patrick Henry would go onto lead the “anti-federalists†who criticized the United States Constitution fearing that it endangered the rights of the States and therefore individual freedoms. His opposition would be instrumental in the adoption of the Bill of Rights. George Washington offered Henry the Secretary of State post in the first Presidential administration, but he declined due to his distaste for the Federalist political agenda. He would eventually change his tune after witnessing the radicalism of the French Revolution and began to understand the necessity of a secure Federal government.

King Henry I was the fourth son of William the Conqueror and the only one to be born in England. Henry succeeded his brother William II as King of England after William’s suspicious death during a hunting trip with his brother, um, Henry (convenient is a word that comes to mind). Henry had to then fight another older brother, Robert, for the throne which ultimately leads to Robert’s imprisonment. After securing his place on the throne, Henry went onto marry a Scot (Edith who would later be renamed Matilda), who was the great-granddaughter of Edward the Confessor, thus placating both the Scots and the Saxons. Henry received two nicknames during his reign “Beauclerc†(which is French for ‘fine scholar’) given his studious nature, and “The Lion of Justice†given his judicial reforms which established a balance for the Anglo-Norman traditions of his kingdom. For the most part, Henry reined during a period of peace and prosperity. He did leave one problem, though: Matilda only gave him two children: William and Matilda, Jr. The heir-apparent, William, died at the age of 17 in an unfortunate drowning accident, and Papa Henry was not too keen on his daughter ascending the throne. He married again (Matilda, Sr. had since died) in an effort to produce another male heir, but was unsuccessful. The throne eventually went to his nephew, Stephen. That would turn out to be a mistake because Matilda Jr. was one fiery bitch.

Henry II was Matilda, Jr.’s son and raised in France until the age of nine, returning with his mother to England in her effort to reclaim the throne. She never quite managed the coup for herself, but Henry II would ascend through her lineage upon Stephen’s death. Henry II had a few things going for him from the English perspective. He was the grandson of Henry I who had done a lot to integrate the Norman-Anglo ways into a fairly stable atmosphere, he was Scottish by way of his maternal lines, and he truly was the rightful heir to the throne. But he also had one glaring problem: his wife Eleanor. She was one tempestuous shrew. Eleanor actively plotted with their sons (Henry, Richard and Geoffrey) to rebel against their father, and she encouraged invasions by the kings of Scotland and France. Such a nuisance was she that Henry II would eventually place her under house-arrest for 15 years. Henry II was a man of reason and intellect like his grandfather and is notable for creating Common Law in England. Only problem was that Henry expected to extend these royal judicial oversights onto the Church. Big mistake. Big, big mistake. Henry appointed Thomas Becket as Archbishop of Canterbury, believing him to have like-minded ideals of exposing the judicial abuses rampant in the Church. What he didn’t expect is that Becket would about-face and side with the Church. Becket went into exile upon hearing the king’s intention to try him for contempt. When Becket returned to England six years later, Henry II screamed (probably rhetorically), “Will someone rid me of this turbulent priest?†Someone took him seriously, because a couple of his knights would go and kill Becket on (gasp) the alter during Church service (thereby martyring him). Needless to say, this event didn’t exactly serve to popularize the King among his people, and he was henceforth publically shamed (forced to walk barefoot through Canterbury, arrive at Becket’s tomb, beg for pardon, and receive a lashing). Not too dignified for a King, huh? His sons Richard I and then John I would succeed him in that order.

King Henry III was John I’s son and Henry II’s grandson. He inherited the throne from his father at the age of nine during another one of those pesky Civil Wars the English like so much (thanks, Dad). Not only was he an ineffective ruler, but he went through money like water after several unsuccessful invasions into Wales and France, and prompted rebellions among the barons (who forced him to limit his powers by signing the “Provisions of Oxfordâ€). The first Parliament (or so considered) convened during his reign, in reaction to this repudiating king. The Baron’s War would ensue leading to the king’s capture and his ultimate escape from captivity orchestrated by his son, Edward, who would eventually succeed his hapless father.

Known also as Henry of Bolingbroke, Henry IV ascended to the throne after his cousin Richard II was deposed (this Henry was the grandson of Edward III). He immediately had to deal with rebellions by both the Welsh and those closer to home and his reign was riddled with plots against him. There’s nothing too notable about Henry IV other than his participations in the on-going Crusades and the War of the Roses, but really didn’t accomplish much. He was also the first native English-speaking king (his predecessors had spoken French).

King Henry V was the son of Henry IV and ascended the throne upon his father’s death. He is known as one of the greatest of all English monarchs and a bane to the French existence. First, Henry V successfully seized the northwest French post, Harfluer. It was an uneven battle and so a massive victory, as the French outnumbered the English by thousands. It was a heady victory for the young king who was met with much fanfare after returning to London. He wasn’t done yet, though. In 1420, he returned to capture Normandy which resulted in the signing of the Treaty of Troyes, naming Henry the heir to the French throne. He celebrated by marrying the daughter of the then-King of France, Charles VI. Her name was Catherine, and she would bear Henry, a son soon to become King Henry VI (and soon to undo his father’s fine work). Henry V’s life was cut short in his mid-30s (struck down by dysentery).

Henry VI not only ascended to the English throne at the age of nine-months, but at the ripe old age of one, he also was king of France. Too young, his uncles would serve as regents and more royal family members would crawl out from the woodwork with their greed for power. About the only good that came out of this naive king’s reign was a passion for education and building (Eton College and King’s College were erected during his time). Turns out, Henry VI’s biggest problem would be a French peasant girl by the name of Joan of Arc. According to her story, which she shared with the Dauphin of France, the voices of the Saints Michael, Catherine and Margaret told her that she alone could drive the English out of France. We can just imagine that the poor, hapless Dauphin unable to motivate the French people himself, responded with a resounding “Sweet, dude. Go for it!†So little Joanie throws on her amour, jumps on her white horse, and heads for Orleans. Her zealous faith in the “Lord’s wishes†and her firm belief in her own purpose must have rubbed off on the people who joined her one-person uprising, because the English would eventually exit stage left. (For more on Joan, see the name Joan). The English and the French are still amidst the 100 Years’ War, but we are nearing the end now. Henry VI mad a terrible mistake by not taking France’s offer of Normandy and Aquitaine if they would just get the hell out, because the French would eventually recapture all of their land back. Of course, this was not Henry’s only problem. Back at home, he wasn’t so popular, particularly given the miserable losses to the French. Enter Richard of York (Henry’s cousin) who was seen as an arguably more legitimate heir to the throne than the current king, fast-forward to The War of Roses, in which two distinct lineages fight over the monarchy for the next 30 years. They brought new meaning to the term dysfunction families. And their battles with one another were seriously violent. Henry VI would ultimately be captured and killed, and the Duke of York’s son would become King Edward IV of England, thus transferring the monarchy to a new House (Lancastrians to the Yorks).

The War of the Roses came in with a Henry, and it went out with a Henry. Henry VII waged the last and final battle of this war when he overthrew King Richard III in 1485 and became the first monarch from the House of Tudor (which turned out to be a long-lasting dynasty). Henry VII was the cool-headed, able king who ushered England into the modern era. Although he was a Lancastrian, he was so by illegitimate descent through King John. He united the Yorks with the Lancasters by marrying Edward IV’s daughter, Elizabeth – so now everyone is neatly together under the new House of Tudor, by a little stretch of the imagination. Still, Henry VII was a fine ruler, although not beloved by the people (he kept his distance from the common man). Under Henry VII, the English government came to be more stabilized and centralized and he died leaving a peaceful and prosperous England to his incurable pleasure-seeking, tyrannically arrogant, hot-headed son, none other than the legendary King Henry VIII.

It will be difficult to summarize this one, so we’ll try and stick to the key facts, and the interesting parts. He became king at the age of 17 after his father died. He loved all forms of leisure and pleasure (hunting, food, wine, music, poetry), but most of all, he liked the ladies (he holds the record for royal marriages). His first wife, Catherine of Aragon, gave birth eight times but produced only one surviving daughter (Mary). Intent on a male heir, Henry VIII decided he needed a new wife. All he needed was the pope to grant him an annulment; only problem was that the Holy Roman Emperor was Catherine’s nephew and she had no intentions of letting this happen. The pope, in turn, could not risk upsetting Rome’s ruler, so the pope did nothing. Furious, Henry VIII severed all connections with the Catholic Church of Rome, had an English Archbishop grant his annulment, and married Anne Boleyn (mother to the future Queen Elizabeth I of England). Well, the pope was having none of that and turned right around and excommunicated the king. What did Henry get for all of his troubles? Another daughter [it’s hard not to laugh at this point]. Stubborn Henry then makes himself “Supreme Head†of the Church of England and goes around beheading any dissenters (you’ll notice his penchant for beheading people a little later). “My way or the highway†best sums up this man’s reign. Back to Anne who wasn’t able to produce a son. Henry, frustrated and tired with poor Anne, moves onto her lady-in-waiting, Jane Seymour (he has Anne beheaded on trumped up charges of treason for…get this…unfaithfulness). Now that’s the pot calling the kettle black! Good ole Jane manages to capture one of those Y chromosomes and gives birth to a son, much to Henry’s delight (but she dies 12 days later from complications). Next, enter: Anne of Cleves, a marriage that was prearranged. When they finally meet for the first time in person, the disappointment is mutual. Anne was reportedly plain, boring and acne-scarred. Henry was no Don Juan himself at this point in his life, grossly overweight and generally nasty. He had that one annulled seven months later, and those he could find to blame for the disastrous pairing were promptly beheaded. Anne of Cleves got to keep her head, and Henry did pay spousal support. After Anne of Cleves came Catherine Howard, a beautiful 18 year old (to Henry’s 49). Enamored with the young sprite at first, Henry wasted no time demanding “Off with her head!†when he learned of her extramarital affairs. Last but not least, we have Catherine Parr (the man liked the name Catherine, apparently). She, too, was young (31), but married the fat old king more from a sense of duty than an aspiring interest in social status and wealth, and she was good to him. She was the one that was there to the end, and he named her Regent before dying at the age of 55. Detestable in so many ways, you have to admit, Henry VIII was one colorful character.